How can we explore a ‘global history’ for the many?

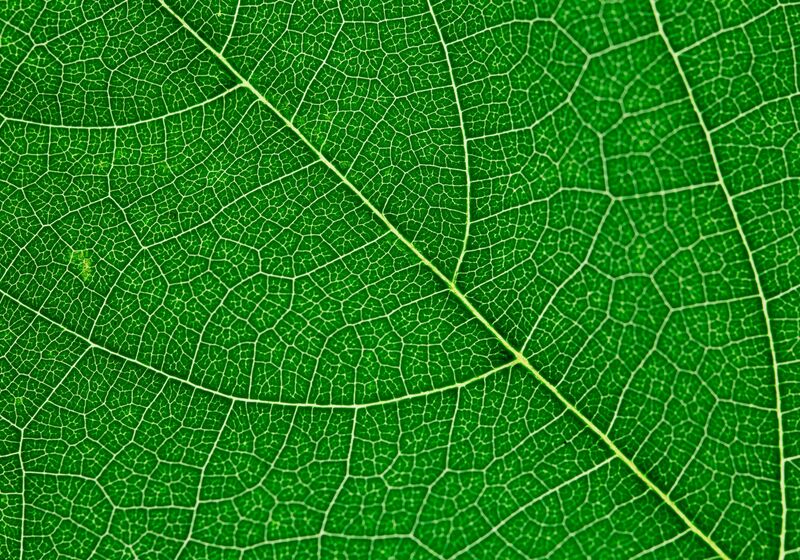

Queen Mary Psalter, calendar scene for August showing three men reaping, with a farmer directing them. Courtesy British Library, Royal 2 B. VII, f.78v

Ambitious new research network strives to take international lead on neglected aspect of medieval study.

By Joanne Dodd

A global history of medieval peasant life is, on the face of it, hard to conceive.

“Who could be less global than a peasant, whether toiling in the rice fields of China, or driving the plough through the heavy clays of northern Europe?” says John Arnold, Professor of Medieval History at the University of Cambridge.

Yet, like other strands of global history, medievalists are attempting to show their discipline can be thought about in global contexts.

An ambitious network of researchers, led by Professor Arnold and Dr Rob Portass, Assistant Professor of Early Medieval History, is now exploring this relatively new field of study to probe the unexplored relationships between rural peasants and larger global forces.

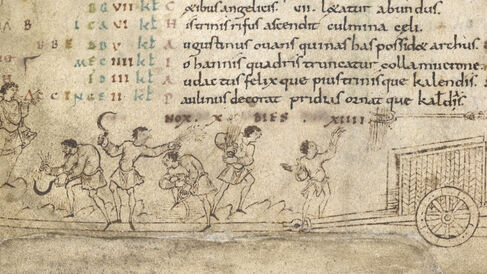

The Julius Calendar and Hymnal, calendar page for August: farm workers harvesting corn. Courtesy British Library, Cotton Julius A. VI, f.6v

A global network

“We are keen on this idea of connections, which may not be visible to the people in the locality – just as in the production of global goods today – but with which they are part of something greater.”

“For example, one of the biggest markets for English wool producers in the 13th century was North Africa. You can tell that story in a global sense in terms of merchants and ships. But you actually start with peasants and artisans of a lower status producing things which feed this global network.”

A landmark collection of essays on The Global Middle Ages (Past and Present, 2018) set the agenda in this nascent field. Yet, as Prof Arnold explains, “it was primarily about the movement of very elite ideas and goods. It is only speaking to 2 or 3 percent of the population at any time in history.

“Our starting point was, what does it mean to think about this from the point of view of ‘the everybody else’?”

This 15-strong network of historians and archaeologists draws together Cambridge colleagues - Caroline Goodson, Jason Hawkes, and Ling Zhang – with other pre-1600 medieval scholars from prominent UK and international institutions.

The group’s expertise is geographically expansive, ranging far beyond England to China, Spain, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and more.

“It's incredibly broad and it's trying to be,” says Arnold. “I'm most interested in global history when it prompts the possibility of comparison.”

Peasants are, for example, largely understood as people who farmed for their survival. The production of excess crops for trade was beyond their reach. Yet through comparison, “you can show peasants in different areas, who manage to produce not simply subsistence, but things that are going to local or higher markets.”

The group’s panoptic approach is only the starting point. The aim is to pinpoint available source material, and to gather together existing knowledge and approaches, to identify promising areas for further research.

“We are exploring the possibilities, not attempting to create a history of the global peasantry in the medieval world.”

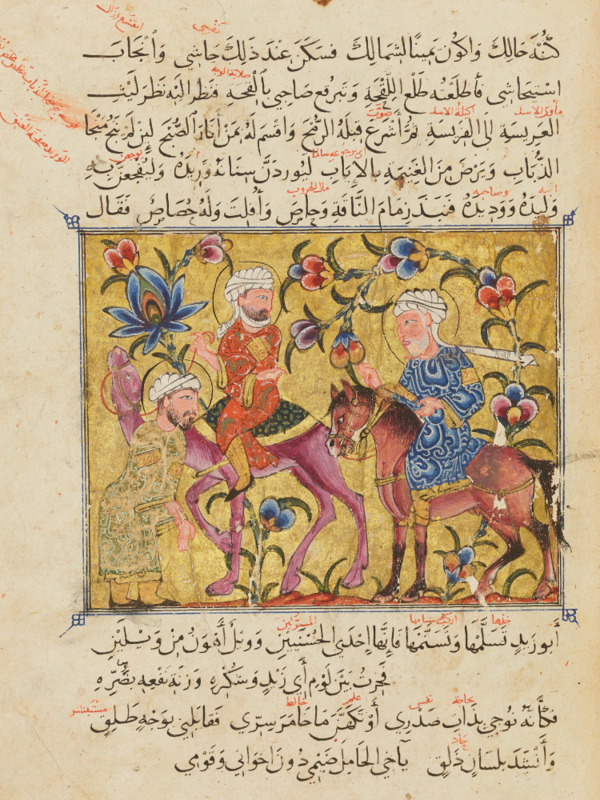

Maqamat (‘Assemblies’), (MS. Marsh 458 fol. 45a). Image: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Creative Commons licence CC-BY-NC 4.0

Archival limitations

But the question is: where will the written record allow the network to see non-elite people?

“We're realising what we're not going to be able to do,” says Arnold. “Late medieval England has more surviving records than almost anywhere else in Western Europe, apart from maybe Catalonia. Late medieval China also has a wealth of surviving sources.

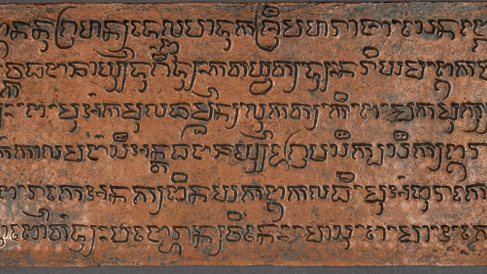

“Yet in some parts of Asia, for example, you have no written record other than what was carved onto stelae [stone tablets]. Or in what would now be eastern India, certain land transfers were copied onto copper plates.”

Old Javanese charter recording the digging of a canal in Pabuharan. British Library, Ind. Ch. 57 (A), f. 1r.

"Other forms almost certainly existed in the medieval period, but the climate mitigates against archival survival.”

The burgeoning network was unable to find anybody working on the social history of sub-Saharan Africa.

“There just isn't any local source material that lets you do that for these medieval centuries,” explains Arnold. “But I'd be keen to talk to people working on Africa, potentially on a later chronology.”

An innovative approach

Not only is this an emerging field of study, but the group is also pursuing innovative methods. “We are consciously trying to act more like a research network of scientists,” says Arnold.

Whereas current literature might start by comparing findings, this network aims first to consider the nature of source material. “If evidence bases are very different, are we still confident that comparisons can be drawn?” says Arnold.

“Can we address these differences through more collaborative working? I don't think that's been done so much by historians.”

This innovative thinking emerged from a conversation with a Geography Department colleague. He had observed that humanities and social science scholars undertaking interdisciplinary work often felt like they had to become expert in the other discipline.

“But you almost never can,” says Arnold. “What you need to do is have better conversations within a safe space across disciplines.

“I think that, particularly in the humanities, we struggle with being told to research like scientists. It can feel rebarbative.

“But to meet this challenge of getting out of your silo of knowledge, you don’t have to become experts in everything. You just need to find ways to have more productive conversations with other experts.”

What's next?

The network has finished its first year of funding, hosting a series of in-person and virtual meetings. Past and Present – the premier journal for social history in England – has committed to fund a concluding conference, which will hopefully inform a special edition for the publication.

The group is not trying to produce a definitive global history, but with its ambitious collaborative work to facilitate “more viable cross-cultural conversations”, they are pursuing a blueprint for future research.

Professor John H. Arnold

John Arnold was elected to the professorship of medieval history at Cambridge in 2016. He is also a Fellow at King's College. He has previously worked at the University of East Anglia and Birkbeck, University of London. He studied at the University of York, gaining a BA in History, and a D.Phil. in Medieval Studies.

His most recent publication, The Making of Lay Religion in Southern France, c. 1000-1350, was published in 2024 with Oxford University Press.

HSS Research Framework

This project is supported by our Research Framework, facilitating interdisciplinary connections